The Process of DOMESTICATION:

How to wipe out an indigenous population, subculture, ethnic group, wild population, or wild species.

As is usual among social humans, there is bitter conflict over “who is right” concerning the history of European – Tasmanian conflict. I could not care less about these social battles; arguments are not about the facts, but about who “owns” history. What does interest me is a pattern of “knocking off” small populations of wild humans, by the reduction of females allowed to reproduce with “wild males.” This pattern applies to the collision of peoples and cultures, in which one is powerful, numerous and RUTHLESS and the other is an indigenous population sheltered by geography from contact with human predators for hundreds to thousands of years. This process has been repeated countless times around the globe.

The Pattern:

1790-ish: British and Americans arrive to hunt seals in the Bass Strait.

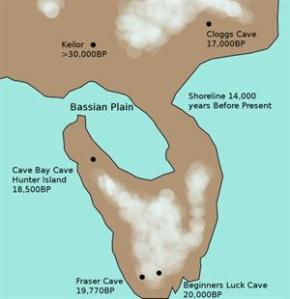

1800-ish Seal hunters are dropped off on uninhabited islands in Bass Strait, staying November to May, the seal hunting season. Sealers establish camps on islands close to Tasmania and make contact with Aboriginal Tasmanians, who had been isolated from their origins in Australia for 8 – 10,000 years.

Trade develops – Tasmanians want dogs & food items; sealers trade for kangaroo hides. No surprise – a trade in Aboriginal Tasmanian women developed: women were excellent seal and bird hunters. Some women were purchased outright, others were “gifts.” Some sealers raided coastal Aboriginal settlements and abducted women.

Each seal hunter “required” 4-5 women to work for him as hunters. The women were marooned on uninhabited islands, and if not enough seals had been killed by the time the sealer returned, the women were brutally beaten and “stubborn” ones killed.

By 1810 the seal population was severely reduced and the hunters moved on; some remained with Aboriginal women they had “married.” Children of these mixed European / Aboriginal reproductions survived while native children stopped being conceived.

Tales are remembered of women who “went rogue,” attacking and killing the sealers because of the brutality they suffered. Female slaves became a force against white authority and fought in conflicts. Women who fought back, resisted enslavement, orproved too difficult to be “domesticated” were eliminated.

After mere decades the number of Aboriginal Tasmanian women declined: it is reported that by 1830 only 3 Aboriginal women remained in northeast Tasmania, along with 72 men. This lack of females made it impossible for Aboriginal Tasmanians to reproduce in enough numbers to survive as a distinct and original population.

Domestication depends on juvenalization (neoteny) – a brutal, but simple, process. Select “tame” females for reproductive use: Childlike traits of obedience, passivity, and easy manipulation and handling are valued by “captors” just as tame traits are valued in the selection of wild animals for domestication.

The idiotic European belief that dressing up indigenous people in “white” clothing will magically convert them into being “tame” or “domesticated.”

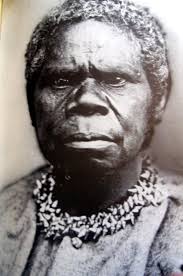

Truganini ca. 1812-1875

Her life and image have been exploited, like a freak in a carnival sideshow or like the head of a trophy animal hung on the wall.

Her life and image have been exploited, like a freak in a carnival sideshow or like the head of a trophy animal hung on the wall.

___Article by: Aaron Greenville and Paddy Pallin

Will we hunt dingoes to the brink like the Tasmanian tiger?

The last Tasmanian tiger died a lonely death in the Hobart Zoo in 1936, just 59 days after new state laws aimed at protecting it from extinction were passed in parliament. But the warning bells about its…

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT /AARON GREENVILLE RECEIVES FUNDING FROM AUSTRALIAN POSTGRADUATE AWARD AND PADDY PALLIN SCIENCE GRANT FUNDED BY HUMANE SOCIETY INTERNATIONAL, ROYAL ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF NSW. GLENDA WARDLE RECEIVES FUNDING FROM THE AUSTRALIAN RESEARCH COUNCIL

A DEAD DINGO IN 2013 (LEFT) AND A TASMANIAN TIGER, LAST SEEN IN THE WILD IN 1932. DINGO PHOTOGRAPHY BY AARON GREENVILLE; A HUNTED THYLACINE IN 1869, PHOTOGRAPHER UNKNOWN.

The last Tasmanian tiger died a lonely death in the Hobart Zoo in 1936, just 59 days after new state laws aimed at protecting it from extinction were passed in parliament. But the warning bells about its likely demise had been pealing for several decades before that protection came too late – and today we’re making many of the same deadly mistakes, only now it’s with dingoes. Earlier this month the Queensland government announced it would make it easier for farmers to put out poison baits for “wild dogs”. In Victoria, similar measures have already been taken. Lethal methods of control have lethal consequences. It is time to rethink our approach in how we manage our wild predators.

A deadly history lesson

(A very familiar impasse to those of us in Wyoming who want the Wolf to retain its natural status as top predator in our state versus cattle and sheep ranchers who demonstrate a pathological fury against the wolf and want it eliminated from Wyoming (again.)

Commonly known as Tasmanian tigers because of their striped backs, thylacines were hunted due to the species alleged damage they were doing to the sheep industry in the state. However, the thylacine’s actual impact on the industry was likely to have been small.

Instead, the species was made a scapegoat for poor management and the harshness of the Tasmanian environment, as early Europeans struggled implementing foreign farming practises to the new world.

The tiger [thylacine]… received a very bad character in the Assembly yesterday; in fact, there appeared not to be one redeeming point in this animal. It was described as cowardly, as stealing down on the sheep in the night and want only killing many more than it could eat… All sheep owners in the House agreed that “something should be done,” as it was asserted that the tigers have largely increased of late years. – The Mercury, October 1886.

More than a century later, and it’s now the dingo in the firing line.

Since 1990, the number of sheep shorn in Queensland has crashed 92 per cent, from over 21 million to less than 2 million. Although there have been rises and falls in the wool price and droughts have come and gone, it’s the dingoes that have been the last straw. – ABC Radio National, May 2013

An ancient predator vs modern farmers

Producing sheep is an incredibly tough business, with droughts, international competition and volatile markets for wool and meat – mostly factors that are well beyond the control of an individual farmer.

Dingoes are seen as one of the few threats to livelihood that producers can fight back against. As a result, the dingo has experienced a severe range contraction since European settlement and there is mounting pressure to remove the dingo from the wild, despite dingoes calling Australia home for 4000 years.

Dingoes are now rare or absent across half of Australia due to intense control measures. While they are more common in other areas, we have seen how species populations can collapse quickly. For example, bounty records from Tasmania showed the thylacine population suddenly crashed in 1904-1910 due to hunting pressure from humans.

Will the dingo’s demise be like that of the thylacine? We simply do not know, but the social conditions and a rapidly changing environment mirror the story of the thylacine.

(Source: aspergerhuman.wordpress.com)

No hay comentarios.:

Publicar un comentario